HOW IT ALL STARTED

This interactive timeline is your guided tour through nearly 80 years of neighbors living united in Baytown and Chambers County. From our beginnings as a small Community Chest in 1946 to today’s regional United Way serving 11 ZIP codes, you’ll find key moments in campaigns, disaster response, health initiatives, ALICE-focused work, and more. Click into each decade to explore stories, photos, and milestones that show how local generosity has shaped our community—and how those same values are leading United Way of Greater Baytown Area & Chambers County into the future.

The 1940s

New industry and wartime production brought jobs, and with them a surge of families looking for work, housing, schools, and medical care. Neighborhoods filled in, traffic picked up, and what had once felt like a small town began to function more like a growing city.

Local churches, clubs, and small charities did what they had always done—passed the hat, organized drives, and helped neighbors one family at a time. But the scale of need was different now. More workers meant more injuries and sickness. More children meant more pressure on schools and youth programs. The community’s generosity was real, but it was scattered and sometimes stretched thin.

Across the country, a new idea was gaining momentum: instead of every group raising money on its own, communities could pool their giving into a single “community chest” and share those funds across local agencies. In Baytown and the surrounding Tri-Cities, leaders were watching that model and beginning to ask whether something similar might help here.

This moment is the backdrop for everything that follows in the 1940s. Before there was a charter or an office or even a name, there was a fast-growing industrial town, rising need, and a community starting to imagine a more organized way to take care of its own.

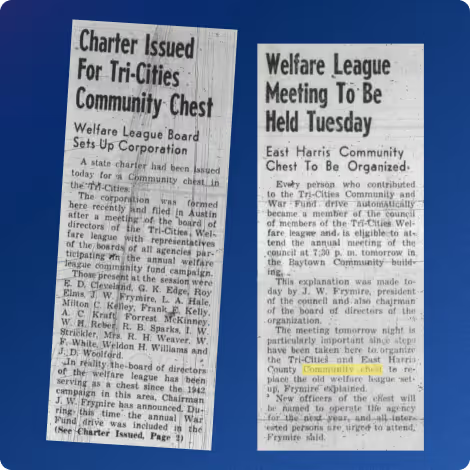

In 1946, before there was a United Way, there was a simple but bold idea: what if the Tri-Cities and East Harris County came together to support all their charitable needs through one common fund? That year, community leaders secured a charter for the Tri-Cities and East Harris County Community Chest, the direct ancestor of today’s United Way of Greater Baytown Area & Chambers County.

Fresh out of World War II, the region was growing fast. New families, new plants, and new neighborhoods were arriving faster than social services could keep up. Churches, youth programs, and health agencies were each running their own small campaigns, competing for attention and dollars. The Community Chest promised something different: one united appeal that would make it easier to give and easier to help.

From the start, the Chest was built on partnerships. Industrial leaders, small business owners, pastors, teachers, and civic volunteers sat at the same table, asking one deceptively simple question: “What does our community need most, and how can we provide it together?” That spirit of collaboration—of neighbors pooling resources to meet shared challenges—became the DNA of the organization.

Today, when United Way talks about living united, that language traces back to this moment. The 1946 charter wasn’t just a legal document; it was a promise that this community would not leave its most vulnerable neighbors to struggle alone. It was the first step in a story that now stretches across eight decades of local impact.

First post-war campaign raises roughly $45,000, establishing a baseline for unified community fundraising.

In the years 1946–1947, the brand-new Tri-Cities and East Harris County Community Chest put its bold idea to the test. The charter was signed, the vision was clear: one united campaign to support many causes. Now the question was simple but risky—would the community say yes?

Coming out of World War II, families across Goose Creek, Pelly, and Baytown were rebuilding their lives. Plants were hiring, neighborhoods were growing, and local agencies were seeing more people at their doors than ever before. Until then, each charity had largely gone it alone, running separate drives and hoping their message would cut through the noise.

The Community Chest asked residents to try something different. Instead of many small appeals, volunteers launched a single, unified campaign, inviting everyone to give what they could to one common fund. The goal—raising roughly $45,000—was ambitious for the time. Plant workers, shop owners, teachers, and retirees all had to decide whether they trusted this new way of giving.

They did. Bit by bit, pledge by pledge, the community met the challenge. That first successful campaign did more than hit a number. It proved that people here believed in shared responsibility—that by pooling their gifts, they could reach farther than any one effort alone.

Today, when United Way of Greater Baytown Area & Chambers County talks about bringing people and resources together, the roots of that promise go back to this moment. The 1946–1947 Community Chest drive is where our tradition of united fundraising truly begins.

Not long after the Community Chest was chartered in 1946, neighbors around the Tri-Cities started to notice a simple, striking image appearing in newspaper ads and on campaign materials: a small red feather.

That red feather wasn’t chosen at random. Across the country, Community Chest campaigns were using it as a symbol of shared responsibility and care. By adopting the red feather, the Tri-Cities and East Harris County Community Chest was making a statement: we are part of a larger movement of communities uniting to help their neighbors.

Locally, the feather did exactly what it was meant to do. It caught the eye in shop windows, on posters in plant break rooms, in church bulletins, and in the pages of The Baytown Sun. Volunteers wore red feather pins on their lapels as they asked friends and coworkers to give. For many families, the annual “red feather drive” became something they recognized at a glance—even if they didn’t yet know every agency it supported.

The symbol helped people connect the dots. If you saw a red feather next to the name of a youth program, a clinic, or a family service agency, you knew that program was part of a bigger story—that your Community Chest dollars were at work there. It made an abstract idea feel tangible and familiar.

Over the decades, the red feather would eventually give way to the now-iconic United Way Circle of Hope logo. But the heart behind it never changed. The red feather era is where Baytown’s habit of rallying around a shared symbol of caring truly begins—a visible reminder that when this community stands together, no one has to face hard times alone.

In the late 1940s, as the Community Chest was still finding its footing, one name began appearing again and again in campaign photos and newspaper clippings: Humble Oil & Refining Company. Early check presentations from Humble weren’t just generous gestures—they were a clear signal that Baytown’s largest employers saw themselves as partners in building a stronger community.

Those photos tell a powerful story. Plant managers and company representatives stand shoulder to shoulder with Community Chest volunteers, handing over checks that represented not only corporate dollars, but the combined giving of hundreds of employees. For workers and their families, it sent a simple message: the place that provides your paycheck is also invested in your neighbors’ well-being.

Humble’s leadership helped legitimize this new idea of a united fund. If a major industrial employer trusted the Community Chest to distribute its charitable dollars wisely, others felt more confident joining in. Smaller businesses followed suit. Civic groups and churches deepened their involvement. The annual campaign became less of a risky experiment and more of a shared tradition.

This early partnership also planted the seeds of a culture that still defines United Way today: workplace giving. When employees saw pledge cards at the refinery or heard campaign updates at safety meetings, giving to the Community Chest became part of what it meant to be part of the Humble workforce.

From the very beginning, corporate partners were not just donors—they were co-builders of the safety net. Humble Oil’s early support helped anchor the Community Chest era and set a lasting expectation that strong companies help create strong communities.

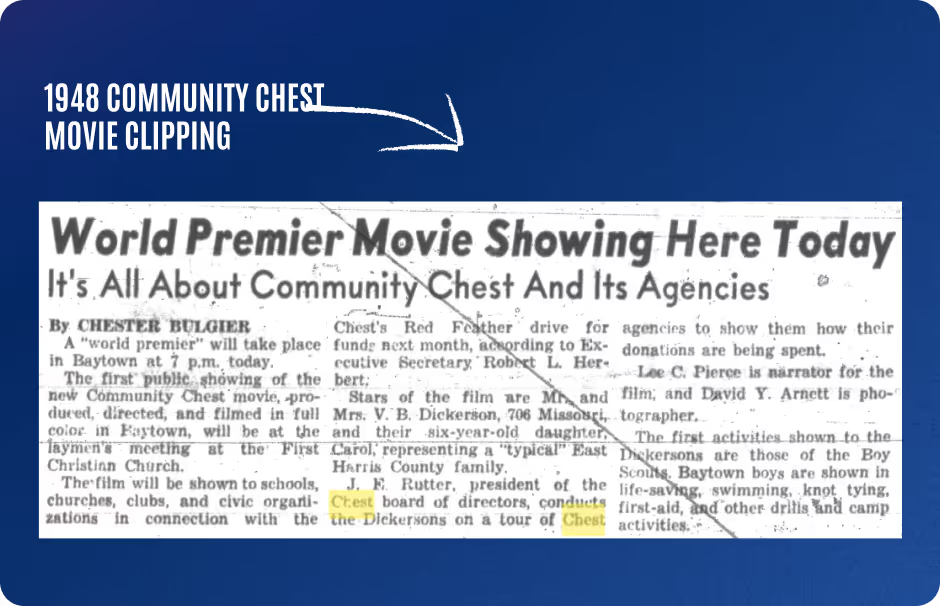

Telling the Story on Film

In 1948, the Community Chest did something remarkably forward-thinking for its time: it stepped into the world of film. Instead of relying only on speeches, brochures, and newspaper columns, leaders commissioned a color movie called “All Because They Care” to show, in living pictures, what Community Chest support meant for local families.

The film followed the work of agencies funded by the Community Chest—children laughing and learning in safe programs, nurses visiting patients who couldn’t afford care, volunteers making sure food and clothing reached those who needed it most. For many viewers, it was the first time they had actually seen the impact of their giving, rather than just reading about it in a campaign flyer.

Copies of All Because They Care were shown in schools, churches, civic clubs, and workplace gatherings. Teachers used it to help students understand what it means to care for neighbors. Civic groups showed it before meetings to spark discussion. Plant managers screened it for employees as part of the annual campaign, helping workers connect their pledge cards to real lives in their own community.

By investing in a film, the Community Chest sent a clear message: you deserve to see where your dollars go. It was an early expression of transparency and accountability that mirrors United Way’s values today.

Since the beginning, United Way has always been an innovation leader in telling its story. Long before digital media or social networks, the Community Chest was already using the tools of its time—projectors, reels, and a bright color film—to help Baytown and Chambers County understand a simple truth: when people care enough to give together, everything that follows is “all because they care.”

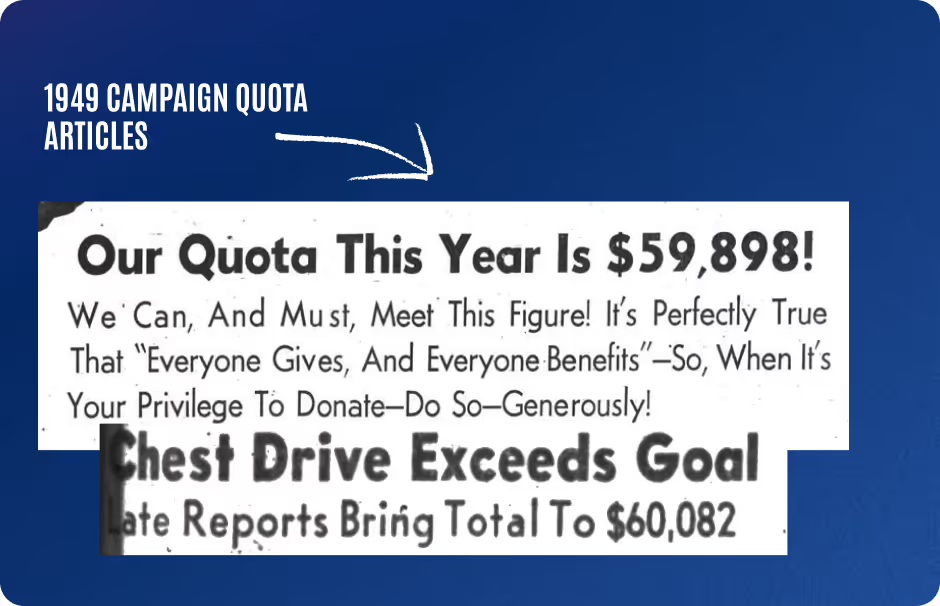

By 1949, the Community Chest was no longer a fragile new idea. Two strong campaigns were behind it, agencies were relying on its support, and families across the Tri-Cities had begun to see the difference a united fund could make. So that year, leaders made a bold choice: they raised the campaign goal to $60,000.

On paper, it was just a higher number. In practice, it was a statement of faith in both the community’s generosity and the growing unified campaign model. Needs were increasing—more families needing medical care, more children seeking safe places to learn and play, more neighbors facing hardship in a rapidly changing postwar economy. If the Community Chest was going to meet those needs, it couldn’t stand still.

Raising the goal meant asking everyone to stretch. Volunteers had to knock on a few more doors and schedule a few more talks with civic clubs. Workplace campaigns needed more employees to sign pledge cards, or for those who could to give just a little bit more per paycheck. It called on residents to see their community not as it had been, but as it was becoming—larger, more complex, and more in need of shared support.

The 1949 goal also quietly did something powerful: it normalized growth. Instead of treating each campaign as a one-off effort, the Community Chest framed its work as a continuing responsibility that would evolve alongside Baytown and the surrounding area.

The picture: a young organization—and a young city—choosing not to play it safe. By setting a $60,000 target, the Community Chest invited the community into a bigger vision of what they could accomplish together when everyone gave a little more to care for their neighbors.

By 1949, the Tri-Cities—Goose Creek, Pelly, and Baytown—had grown up side by side, sharing industry, schools, and families. That year, voters made a defining choice: to consolidate into a single city, Baytown. For the Community Chest, it was more than just a new name on the map; it changed the shape of the mission.

Suddenly, the organization that had been designed to serve loosely connected towns now found itself serving a single, rapidly urbanizing community. Neighborhoods that once thought of themselves as separate were officially united—along with their challenges. Housing shortages, health needs, youth programs, and poverty didn’t stop at the old city limits, and now neither did the Community Chest.

The new city boundaries sharpened the question: “What does it mean to care for all of Baytown?” The Community Chest began to think in broader terms—about citywide campaigns rather than scattered appeals, about coordinating services instead of duplicating them. Industrial partners like Humble Oil didn’t just support a town or a plant; they supported the whole community.

For United Way’s story, the 1949 consolidation marks a turning point. It’s the moment when “our community” stopped being three neighboring towns and started being one shared Baytown, with one shared fate. The Community Chest—and later United Way—would become one of the most consistent threads running through that story, helping residents weather booms, busts, storms, and social change together.

The 1950s

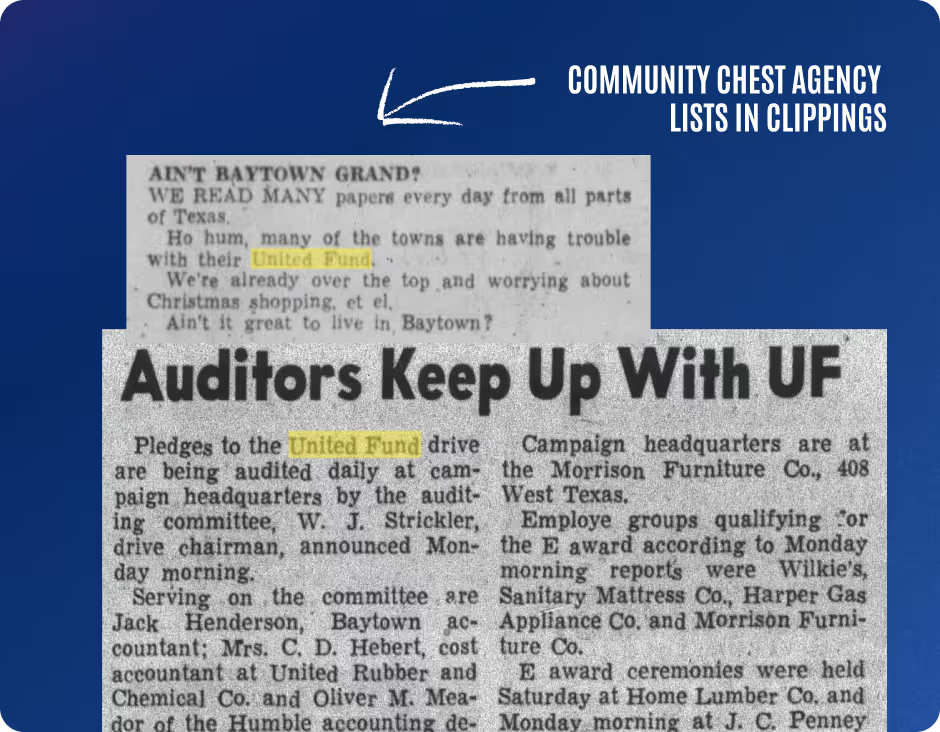

By the early 1950s, the Baytown & East Harris County Community Chest was no longer an experiment—it was an institution. The organization had secured federal tax-exempt status by 1950, anchoring it as a permanent part of the local nonprofit landscape.

City directories list the Community Chest alongside everyday fixtures like churches, schools, and shops, with a named executive secretary and office address—proof that by mid-century, “the Chest” had become a familiar part of community life.

This was the era when the basic pattern of a United Way year really took shape: one coordinated campaign instead of dozens of separate appeals, volunteers fanning out through plants, offices, and neighborhoods, and a single shared pool of funds sustaining a mix of local agencies—child care, health services, youth programs, and family support. Nationally, Community Chests and emerging “United Funds” were moving toward unified workplace drives and payroll deduction, and Baytown’s growing industrial workforce fit right into that model.

For many families, the 1950s campaigns were their first real encounter with organized philanthropy. You might hear about the drive at work, see a story in newspaper, or find a volunteer at your door with a pledge card and a simple message: if everyone gives a little, every agency can keep its doors open. Those dollars turned into very practical things—nurses’ visits, counseling hours, youth activities, food, and rent help at a time when the region was still adjusting to rapid post-war growth.

Think of the 1950s as the decade where the Community Chest “settles in.; quietly building habits, trust, and systems—annual drives, agency relationships, a small professional staff—that will make everything that comes later possible. It’s the decade where neighbors start to assume that, of course, there will be a Community Chest campaign in the fall, and of course, it will be there when someone they know needs help.

In the early 1950s, the Community Chest began to look less like an experiment and more like the backbone of Baytown’s helping network. Each new campaign brought additional agencies onto the roster—youth programs, health clinics, family service centers, and organizations that walked alongside people in crisis.

What had started as a small group of core partners quickly grew into a diverse web of services. Children could take part in safe, structured activities after school. Families facing illness or injury could turn to agencies that offered care, guidance, and a path forward. Seniors found companionship, support, and dignity through programs designed just for them.

Adding more agencies wasn’t just about spreading money around. It reflected a deeper understanding of how connected community needs really are. A child’s success at school might depend on stable housing, access to healthcare, or a parent getting help after a job loss. Leaders began to see that no single program could address all of that alone—but a united fund could help sustain many different pieces of the solution.

Inside the Community Chest, volunteers serving on allocation committees pored over agency lists, budgets, and reports, working hard to stretch every dollar. Agency directors sat at the same table, sharing what they were seeing on the ground and coordinating their efforts. The Community Chest was becoming more than a fundraising tool; it was a convener, helping the helpers work better together.

For donors, this expansion meant that one gift now supported an even wider range of impact. The Community Chest truly became what it aspired to be: one fund for many needs, reaching into more corners of Baytown and the surrounding area than ever before.

By the mid-1950s, something subtle but powerful was happening in Baytown and the surrounding area: giving at work was becoming part of everyday life. Instead of relying only on door-to-door asks or club meetings, the Community Chest and growing United Fund leaned into a new strategy—payroll deduction campaigns in plants, schools, and offices.

At the refineries and industrial plants, campaign volunteers stood up at safety meetings and shift changes to explain how even a small amount taken out of each paycheck could add up to vital support for local agencies. Posters went up in break rooms. Pledge cards were passed down long tables in lunchrooms. Supervisors and union leaders often led by example, turning in their own pledge cards first.

Schools and office staff joined in too. Teachers and administrators committed a few dollars each pay period. Bank tellers, clerks, and bookkeepers quietly added United Fund to their budgets. Suddenly, supporting the Community Chest wasn’t just something you did once a year—it was woven into the rhythm of every paycheck.

This shift did two important things. First, it made giving accessible. Not everyone could write a large check, but many people found they could afford a dollar or two per pay period. Second, it built a sense of shared commitment at work. Co-workers could look at campaign posters or thermometers on the wall and know, “We’re doing this together.”

The culture that emerged in the mid-1950s is the foundation of the strong workplace campaign tradition that still fuels United Way today. This shift demonstrates how generosity moved from something occasional and individual to something consistent and collective—a quiet but transformative change in how Baytown and Chambers County chose to care for their neighbors.

On October 25, 1956, Baytown and East Harris County opened the paper to see a number that must have felt both exciting and intimidating: the new United Fund drive was launching with a goal of $143,408. For a town that had started its united giving with a $45,000 post-war campaign, this six-figure target marked a whole new level of ambition.

The Community Chest idea had grown up; by the mid-1950s, the “United Fund machine” was already raising well over $130,000 a year for local health and human service agencies, and the community was ready to push even further.

This wasn’t just another year of “passing the hat.” By 1956, leaders had seen what a united campaign could do—stronger youth programs, more stable health and social services, and families getting help when they needed it most. They also knew the needs were growing. Setting a $143,408 goal signaled more than inflation; it reflected confidence. Campaign chairs, plant managers, and volunteers believed that refinery workers, shop owners, teachers, and families across the Tri-Cities would step up together to meet a shared responsibility.

The answer unfolded in plant gates, school offices, and storefronts across the area. Workplace rallies kicked off with speeches and charts. Volunteers visited civic clubs and church groups, explaining how one gift to the United Fund would support many agencies at once. Ads and editorials in The Baytown Sun urged residents to think beyond their own front doors and see the faces of neighbors whose lives depended on these services.

The Community Chest/United Fund were becoming a major civic engine. A $143,408 goal in 1956 tells you that by the end of the decade, giving through the Fund wasn’t a small side project—it was one of the main ways Baytown and East Harris County took care of their own.

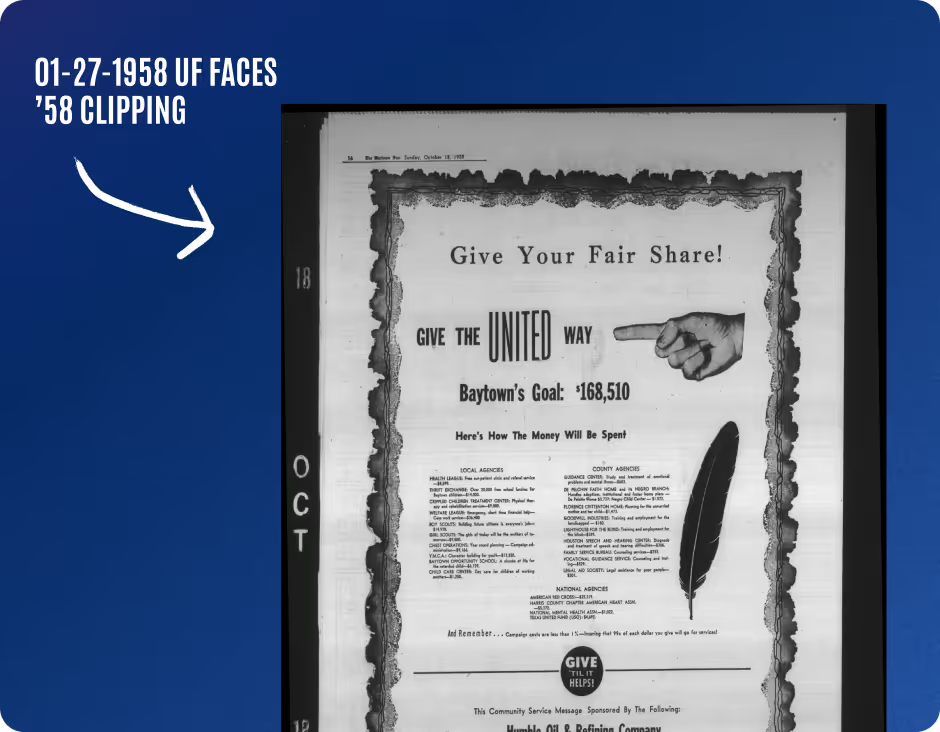

On January 27, 1958, readers of The Baytown Sun opened their paper to find something new in the United Fund coverage: real people, front and center. The “UF Faces ’58” editorial series didn’t lead with dollar totals or campaign charts. Instead, it introduced the community to the children, seniors, and families whose lives were being changed by United Fund–supported agencies.

One week, a story might follow a child finding a safe, nurturing place to go after school. Another might spotlight a senior who no longer had to face loneliness and hunger alone. A third might share how counseling helped a family weather a crisis. Each piece made the same quiet point: behind every pledge card and workplace campaign was a neighbor with a name and a future.

This series marked a turning point in how the united campaign talked about its work. Rather than focusing only on how much was raised, “UF Faces ’58” focused on who was helped. It invited donors to see themselves not just as givers, but as partners in each success story. And it gave agencies a powerful platform to explain why their services mattered in ways that statistics alone never could.

For volunteers and staff, seeing their clients’ stories in print was energizing. It validated long hours and hard decisions, and reminded them that the community was paying attention. For readers, it brought the mission close to home: these weren’t distant problems; they were happening right here, to people who might live on the next street over.

These are the roots of United Way’s modern storytelling. Long before videos and social media, United Fund understood that the most compelling case for giving is simple: meet the faces behind the numbers, and see what your generosity makes possible.

In the late 1950s, a small but important shift began to show up in Baytown’s campaign materials and newspaper ads. Alongside familiar references to the Community Chest and United Fund, a new phrase started appearing: “Give the United Way.”

At first, it might have seemed like just another tagline. But those four words quietly signaled a bigger change. They connected Baytown’s local effort to a growing national United Way movement, one that was standardizing best practices, strengthening accountability, and building a shared identity across communities.

For local donors, the phrase “Give the United Way” reinforced a sense of continuity and trust. It said, in effect, “This is not a one-off drive. This is how we, as a community, take care of each other—year after year.” Whether you saw it in a Baytown Sun ad, on a campaign flyer, or on a poster at your workplace, the words created a consistent message: giving through this united campaign is the way we do good together.

For volunteers and agency partners, the new language hinted at possibility. Being part of “United Way” meant access to shared tools, training, and recognition. It meant knowing that the work in Baytown and the surrounding area was part of a larger story of communities helping communities across the country.

The 1960s

In the 1960s, united giving sinks deep into the bones of Baytown and the surrounding area. The annual campaign isn’t a novelty anymore—it’s part of the rhythm of the year. Fall brings kickoff rallies, pledge cards at work, thermometers in store windows, and updates in the paper charting the community’s progress toward the goal.

Inside plants and offices, participation becomes a point of pride. Scoreboards go up in breakrooms. Supervisors brag about their teams’ generosity. Volunteers learn how to tell the story: one gift to the united campaign supports a whole network of youth programs, health services, and family supports.

As you walk through the 1960s, imagine families who may never read a campaign brochure still feeling the impact—through an after-school program that didn’t close, a counseling session that stayed affordable, a nurse’s visit that made all the difference. This decade may not have flashy headlines, but it builds the quiet, reliable culture of shared responsibility that everything else relies on.

In 1960, the United Fund didn’t just ask for donations—it invited the community into a campaign with personality. “Operation Clean Sweep” became the rallying cry, a playful but serious effort to “sweep” the city for pledges and participation.

Schools, civic clubs, and neighborhoods all joined in. Students helped distribute materials and spread the word. Volunteers turned the campaign into a friendly competition between companies, departments, and even streets. What made Operation Clean Sweep special wasn’t just the dollars raised—though those were significant. It was the sense that everyone, from refinery workers to schoolchildren, had a part to play. Giving to United Fund wasn’t presented as charity from a few; it was the community’s shared responsibility and shared pride.

This is a vivid snapshot of United Way’s core belief: that when people rally around a common goal, they accomplish more than they ever could alone. Operation Clean Sweep foreshadowed later “Day of Caring” events and volunteer-driven campaigns. It showed Baytown what it looked like to live united long before that phrase became a national tagline.

In 1960, the united campaign didn’t live only in boardrooms and kickoff luncheons—it showed up in classrooms, Scout meetings, and family conversations around the dinner table. One of the clearest examples was Good Turn Day, when local Boy Scouts and community members were invited to make a simple promise: do something kind for someone else today—and connect that spirit of service to the United Fund campaign.

Scouts collected food, clothing, and coins in coffee cans and jars. At places like Lee High School, students and teachers heard about the importance of “good turns” and how small acts of generosity add up when a community does them together. In the background, “Give the United Way”–style ads and United Fund messages appeared in The Baytown Sun, reinforcing the idea that caring for neighbors wasn’t a once-a-year event—it was part of who this community was trying to be every day.

Good Turn Day helped children and teens see that they had a real role to play. Even if they didn’t have a paycheck to pledge, they could still serve, still share, still invite others to join in. For adults, watching young people step up was a powerful reminder of why the campaign mattered in the first place: it was about shaping a community where kindness is taught, modeled, and multiplied.

On your history walk, this milestone shows that United Way’s local story isn’t just about big checks and campaign totals. From early on, the movement has been about embedding service into everyday life—teaching generations of young people that a “good turn,” done together and done often, can change the course of a whole community.

In 1961, Hurricane Carla roared across the Texas Gulf Coast, bringing powerful winds and heavy rain that disrupted life across Baytown and the surrounding area. Streets flooded, homes were damaged, and routines were turned upside down. For many families, it was the first time they had faced a disaster of that scale—and they quickly discovered how much they depended on neighbors and community organizations to get through it.

In those uncertain days, United Fund agencies were among the first places people turned. Shelters opened their doors to families who had to leave damaged houses. Relief agencies helped distribute clothing, food, and basic supplies to those who suddenly had none. Health and counseling programs supported residents coping with fear, loss, and the stress of putting their lives back together.

What stood out was how quickly agencies could respond. Because the United Fund supported them year-round, these organizations already had staff, relationships, and infrastructure in place. They didn’t have to start from scratch when Carla hit—they simply shifted into a different gear. United Fund dollars, pledged months earlier by plant workers, teachers, shop owners, and retirees, were already at work when the storm arrived.

Hurricane Carla became an early lesson in resilience for this community. It showed that a united campaign doesn’t just help in “normal” times; it quietly builds the capacity that becomes essential in times of crisis.

The Community Chest response to Hurricane Carla marks the beginning of a pattern that would repeat with later storms like Alicia, Ike, Harvey, and Beryl: when disaster strikes, the agencies supported through united giving are among the first to respond—and United Way is already there, woven into the fabric of the community’s recovery.

On October 5, 1964, families opened The Baytown Sun to see a familiar community leader speaking in a slightly different role. The local school superintendent wasn’t just talking about grades, buses, or football schedules—he was urging teachers, staff, and families to support the United Fund campaign.

In that public appeal, the superintendent drew a clear line between what happens in the classroom and what happens in the rest of a child’s life. He knew that students don’t leave their worries at the schoolhouse door. Hunger, unstable housing, family stress, and health issues all follow them into their desks and onto the playground. And many of the programs helping families shoulder those burdens—youth services, counseling, health care, emergency assistance—were funded by United Fund.

By putting his name and office behind the campaign, the superintendent did more than ask for donations. He helped people see United Fund as a partner in education. When school employees pledged through payroll deduction, or when families decided to give, they weren’t just supporting “charities” in the abstract—they were strengthening the safety net around students and their classmates.

The message also modeled something powerful for young people: community leaders have a responsibility to step forward when their neighbors are in need. Seeing the superintendent support United Fund so openly told teachers, staff, and parents that this was not just a good cause, but our cause.

This support demonstrates how early and how clearly the education community aligned with the united campaign. Long before “wraparound supports” became a buzzword, school leaders in Baytown were already saying out loud: strong schools need strong community services—and United Fund helps make that possible.

By the fall of 1964, the united campaign in Baytown and the surrounding area felt less like a daring experiment and more like part of the community’s backbone. Each year, neighbors watched the thermometer in the paper climb as reports rolled in from plants, schools, offices, and civic clubs. But that year, the updates told a new kind of story: for the first time, the United Fund drive had passed $200,000.

On the surface, it was just a number. But behind it was something quieter and more powerful than a single “leap”—consistency. Nearly twenty years after the first Community Chest campaign, thousands of people had built the habit of giving together. Workers at the refineries and chemical plants expected to see pledge cards at shift meetings. Teachers and school staff knew the campaign was coming each fall. Small businesses, churches, and clubs had baked United Fund appeals into their annual calendars.

The $200,000 mark didn’t just mean “more money raised.” It meant agencies could plan a little further ahead. Counseling centers could keep staff positions filled. Youth programs could commit to another year of after-school hours. Health and rehabilitation services could say “yes” to more families who needed care. A united campaign at that scale signaled that help in this community wasn’t going to be hit-or-miss—it was something people were choosing to sustain, year after year.

For campaign leaders and partner agencies, crossing $200,000 brought a different kind of pressure than earlier drives. The goal had been reached, but now the question was, What will we do with this level of trust? Donors had said, in effect, “We believe in this system. We’re counting on you to keep it strong.”

This milestone is a snapshot of a community that has settled into united giving as a way of life, and of a United Fund that’s grown big enough to be counted on when neighbors need it most.

By 1965, the united campaign in Baytown and the surrounding area had already seen some impressive years. But that fall, the community did something extraordinary. Headlines declared the latest effort the “strongest United Fund drive in local history,” celebrating not only the dollars raised but the sheer breadth of participation that made it possible.

The success of 1965 didn’t come out of nowhere. It built directly on the momentum of the 1964 campaign, which had just broken the $200,000 barrier. Volunteers came into the new drive a little more confident and a lot more organized. Divisions had clearer goals. Workplace campaigns knew which messages resonated. Agency partners had practiced telling their stories in ways that showed both need and hope.

Across plants, schools, and small businesses, the community stepped up. Some donors increased their pledges, trusting that the united campaign would put their gifts to good use. New donors joined in for the first time, encouraged by coworkers and neighbors. Civic groups sponsored special events. Churches shared updates from the pulpit. The Baytown Sun tracked progress and celebrated milestones along the way.

What made the 1965 drive historic wasn’t just the final total—it was the sense that the community had found its stride. United Fund was no longer proving itself every year from scratch. It had become a trusted, reliable way for Baytown and Chambers County to meet shared needs, year after year.

1965 represents a turning point in confidence. The “strongest drive in local history” showed residents that when they pulled together, they could do more than meet emergencies—they could build a better, more caring community on purpose, and then raise the bar again.

In the late 1960s, United Fund’s story in our community became increasingly visible not just through campaign totals, but through the names and faces of the partners standing beside it. Between 1967 and 1969, headlines and photos highlighted organizations like Lee College, Gulf Oil, Brown & Root, U.S. Steel, and a growing list of civic clubs and churches as leaders in both giving and service.

On college campuses, students and staff at Lee College ran campaigns and volunteered with United Fund agencies, tying education and community service together in practical ways. In the industrial plants, companies like Gulf Oil, Brown & Root, and U.S. Steel organized large workplace drives, often celebrating divisions or departments that hit 100% participation or exceeded their goals. These weren’t quiet, behind-the-scenes contributions—they were moments of public pride, captured in award photos and thank-you ads.

Civic organizations, from service clubs to faith communities, amplified the message. They sponsored events, served on allocation and campaign committees, and helped introduce United Fund to new audiences. When the campaign recognized “top givers” or presented plaques of appreciation, it was really honoring something deeper: a shared belief that strong institutions have a responsibility to help build a strong community.

This period cemented a culture where businesses, schools, and civic groups didn’t just operate in the same town—they owned the well-being of that town together. Their leadership made it easier for everyday residents to trust the campaign, to see that the places where they worked, studied, and worshipped were fully invested in caring for their neighbors.

United Way’s power has always depended on partners who step forward, publicly and consistently, to say: we’re in this with you, and we’re in this for the long haul.

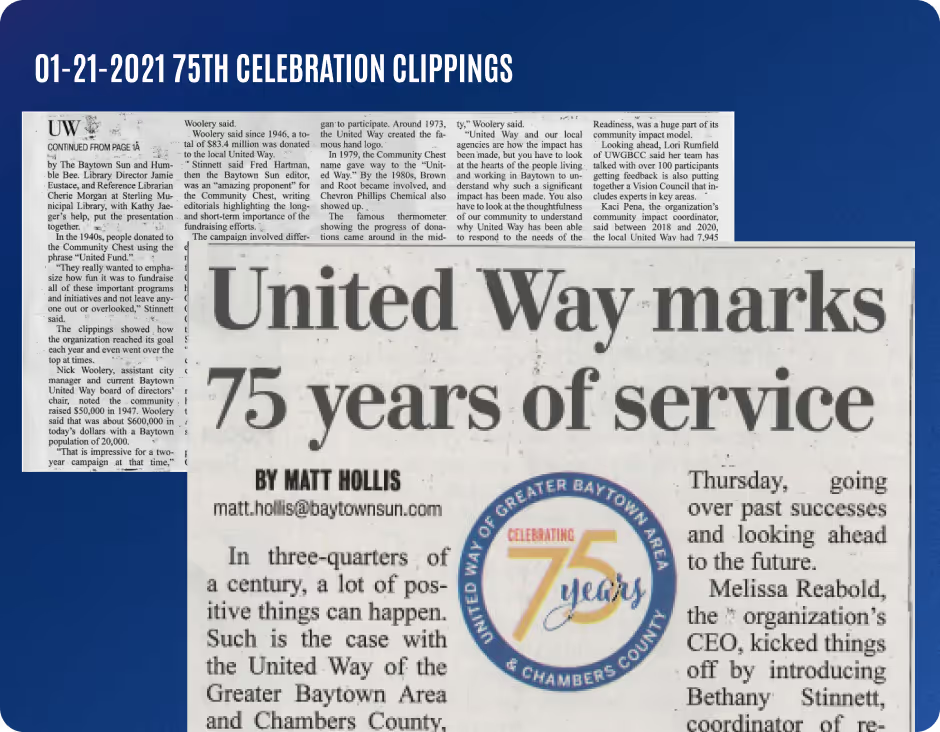

By 1969, the united campaign in Baytown and the surrounding area had come a long way from its early Community Chest days. That year, The Baytown Sun paused to look back, publishing a Community Chest retrospective that traced the journey from small, post-war drives to a strong, community-wide United Fund. It wasn’t just a history lesson—it was a moment of recognition and recommitment.

The retrospective reminded readers of where it all began: red feather campaigns, the first $45,000 drive, and the bold decision to create one fund for many needs. It showed how each decade had added something new—more partner agencies, larger goals, stronger workplace campaigns, and a growing culture of shared responsibility. Side by side with these memories, the paper highlighted contemporary leadership, including Conrad Magouirk, then serving as United Fund president.

Magouirk’s presence in those photos and stories spoke volumes. He represented a new generation of civic leaders stepping into roles once held by the founders of the Community Chest. His leadership symbolized continuity and renewal at the same time: the mission hadn’t changed, but the community was still raising up new champions to carry it forward.

For residents, the 1969 look back was a reminder that the united campaign was not a passing trend. It had become part of the community’s identity—something that had weathered change, grown with the city, and proven its value year after year.

The 1960s were not just a decade of record goals and expanding partnerships, but as a moment when Baytown paused to honor its roots, recognize its leaders, and quietly decide to keep building a more caring community into the next decade and beyond.

The 1970s

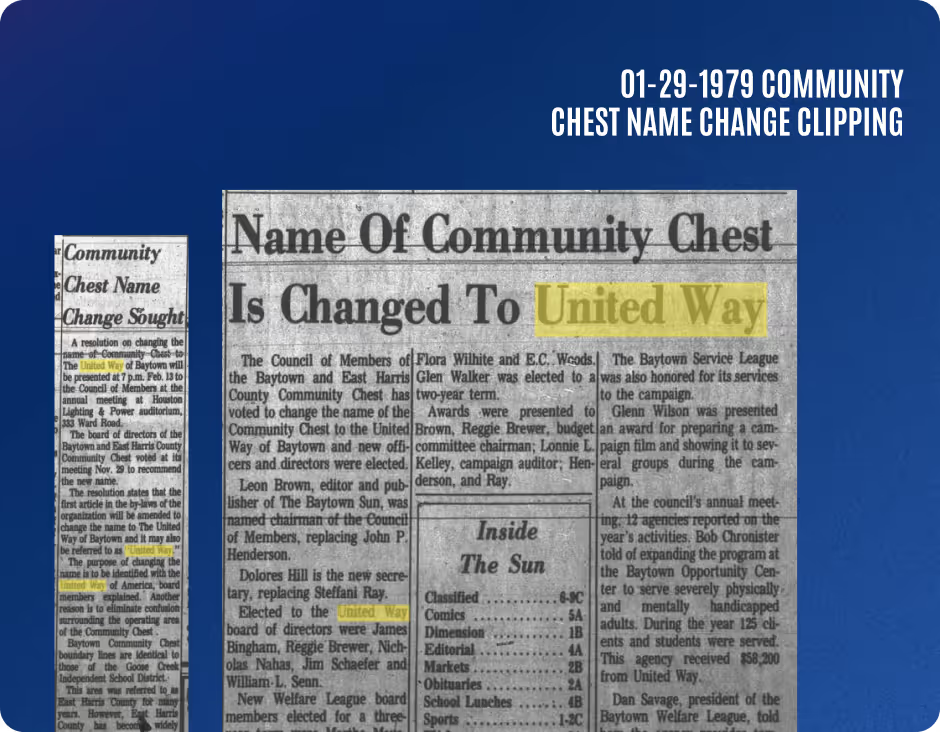

Across the country in the 1970s, the Community Chest and United Fund movement was evolving into something new: United Way. In Baytown, that change became real over the course of the decade and culminated in a 1979 decision to adopt the name “United Way of Baytown.”

Local leaders weren’t just chasing a trend. They were moving from a loosely connected fund drive to a more strategic, accountable community organization. Aligning with United Way brought clearer standards for stewardship, agency review, and reporting to donors, while keeping control in local hands.

For longtime supporters who remembered the early Community Chest days, the shift felt like a natural next chapter. For younger donors, the United Way name and cupped-hands logo signaled a modern, recognizable movement they could trust. The 1970s set the stage for the United Way of Greater Baytown Area & Chambers County we know today—same mission, stronger structure, and a clearer identity as the place where the community comes together to solve problems no single agency can tackle alone. The 1970s was a decade of deepening capacity. United Way’s reach extended further into Baytown and Chambers County, making it increasingly true that wherever there was a need, there was likely a United Way–supported program close by, ready to help.

Throughout the 1970s, the United Way story in Baytown and Chambers County was one of steady expansion. Year after year, campaign charts in The Baytown Sun showed goals edging higher—and meeting or surpassing them. At the same time, the list of funded agencies kept growing, especially in health, youth development, and family services.

What that looked like on the ground was simple but powerful. More families had access to medical care and counseling. More children could join scouting, after-school, and summer programs that kept them safe, learning, and connected. More seniors found companionship, transportation, and support to stay independent. The safety net that had started with a handful of agencies in the Community Chest era now stretched across more corners of the community.

The 1970s also saw United Way leaning further into its role as a coordinator and convener. Allocation committees weighed how to balance support among long-time partners and emerging needs. Agencies began talking more with one another—about referrals, gaps in services, and ways to avoid duplication. The united campaign wasn’t just dividing up money; it was helping to knit together a genuine network of care.

For donors, each new campaign booklet or newspaper insert told a bigger story. The roster of agencies grew longer, but the message grew clearer: when you give here, you’re helping your neighbors at every stage of life. Whether a gift came from a refinery paycheck, a teacher’s salary, a retiree’s savings, or a small business till, it was multiplied through a widening circle of impact.

In the 1970s, something important shifted in how the united campaign was led and seen. Plant managers, refinery executives, bank officers, and other business leaders didn’t just support United Way from the sidelines—they stepped directly into roles as campaign chairs, division leaders, and board members. Their photos and titles began appearing regularly in announcement stories and “thank you” ads throughout the decade.

For the community, this visible leadership meant a lot. When a well-known plant manager or business owner agreed to chair the campaign, it sent a clear message to employees and neighbors: this matters, and I’m willing to put my name and time behind it. That kind of public commitment helped open doors for workplace presentations, special events, and new corporate gifts. It also made it easier for frontline volunteers to make the case: “Our leadership believes in this—and they’re asking us to join them.”

Inside the organization, these leaders brought valuable skills and perspectives. They were used to setting goals, reading budgets, solving problems, and rallying teams—exactly the kind of strengths a growing United Way needed. Serving on the board or as campaign chair gave them a deeper understanding of community needs, beyond what they might see from the plant gate or the office window.

Over time, this pattern created a strong tradition: in Baytown and Chambers County, strong businesses help build a strong United Way, and vice versa. Corporate leaders weren’t just donors—they were architects of the effort, helping to shape strategy, inspire volunteers, and champion United Way’s mission in rooms where big decisions were made.

The 1970s cemented a partnership that still defines United Way GBACC today: industry and business leaders standing shoulder to shoulder with nonprofits and neighbors to move the whole community forward.

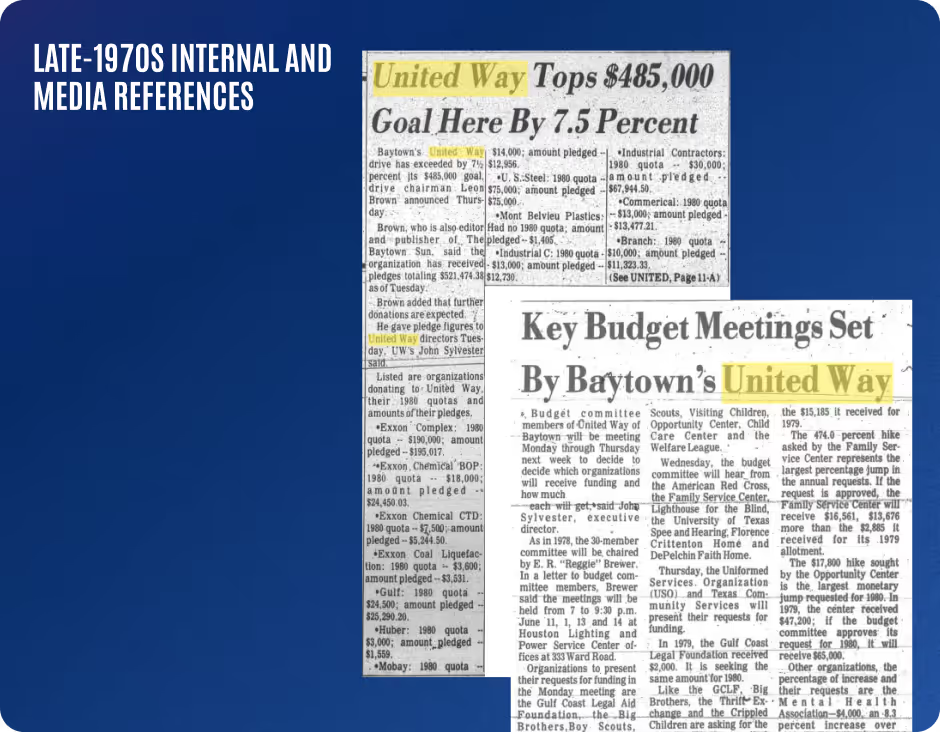

Across the country in the 1970s, the Community Chest and United Fund movement was evolving into something new: United Way. In Baytown, that change became real over the course of the decade and culminated in a 1979 decision to adopt the name “United Way of Baytown.”

Local leaders weren’t just chasing a trend. They were moving from a loosely connected fund drive to a more strategic, accountable community organization. Aligning with United Way brought clearer standards for stewardship, agency review, and reporting to donors, while keeping control in local hands.

For longtime supporters who remembered the early Community Chest days, the shift felt like a natural next chapter. For younger donors, the United Way name and Circle of Hope logo signaled a modern, recognizable movement they could trust. The 1970s set the stage for the United Way of Greater Baytown Area & Chambers County we know today—same mission, stronger structure, and a clearer identity as the place where the community comes together to solve problems no single agency can tackle alone.

By the late 1970s, United Way in Baytown and Chambers County was no longer a small, seasonal effort that ramped up once a year and then faded into the background. Campaigns had grown more complex, the list of partner agencies was longer, and the expectations from donors and the community were higher. To keep up, United Way began to professionalize its staff and campaign systems in a deliberate way.

Instead of relying almost entirely on volunteers and informal processes, the organization invested in clearer staff roles and more structured ways of running the campaign. There were defined timelines, division charts, pledge tracking systems, and standardized materials for workplace campaigns. Staff and key volunteers developed expertise in data tracking, stewardship, and communications—skills that would later prove essential as campaigns grew into the hundreds of thousands and then millions of dollars.

This shift didn’t replace the heart of the work; it strengthened it. Volunteers still played a crucial role, but they were better supported. Campaign chairs had more reliable information at their fingertips. Allocation committees received clearer financial reports. Agency partners could plan more confidently, knowing the organization behind them was stable, organized, and forward-thinking.

For donors—especially corporate and workplace donors—this professionalization built trust. They could see that United Way was treating their contributions with the same seriousness they expected in their own businesses: careful planning, strong systems, and clear accountability.

This milestone marks the moment when United Way quietly laid the backbone for the million-dollar campaigns and complex initiatives that would come in the 1980s and beyond. It’s a reminder that big public successes often rest on less visible decisions: to build good systems, to hire capable staff, and to treat community generosity as something worthy of the very best stewardship.

The 1980s

By the 1980s, United Way of Baytown wasn’t just a campaign you heard about once a year—it was part of the community’s backbone. The united drive was now funding a wider mix of services for children, families, seniors, and people with disabilities, and the work needed a true home base. In this era, United Way put down roots along Decker Drive in Baytown, in the building many people still recognize today—sharing space with partners like the American Red Cross and becoming a visible landmark of local compassion and coordination.

Outside those walls, the decade wasn’t easy. The oil bust of the mid-1980s hit the Houston region hard—hundreds of thousands of jobs were lost across energy and related industries, and many once-stable families suddenly found themselves in shaky circumstances. In a community so closely tied to refineries and petrochemical plants, that downturn showed up as foreclosures, stressed household budgets, and rising demand at local agencies.

Inside the Decker Drive office, United Way’s role evolved from “just fundraising” to steadying the network. Campaign volunteers still rallied in plants and offices, but the conversations sounded different: agencies needed help not only to grow, but to hang on and adapt. United Way convened leaders, listened to emerging needs, and worked to keep counseling, basic needs, and youth programs open for neighbors weathering layoffs and uncertainty.

As you walk through the 1980s, picture that building on Decker as both anchor and crossroads—a place where volunteers, agency directors, and community members gathered to ask, “How do we get through this together?” It’s a decade that shows United Way not only growing up, but learning how to help a community bend without breaking.

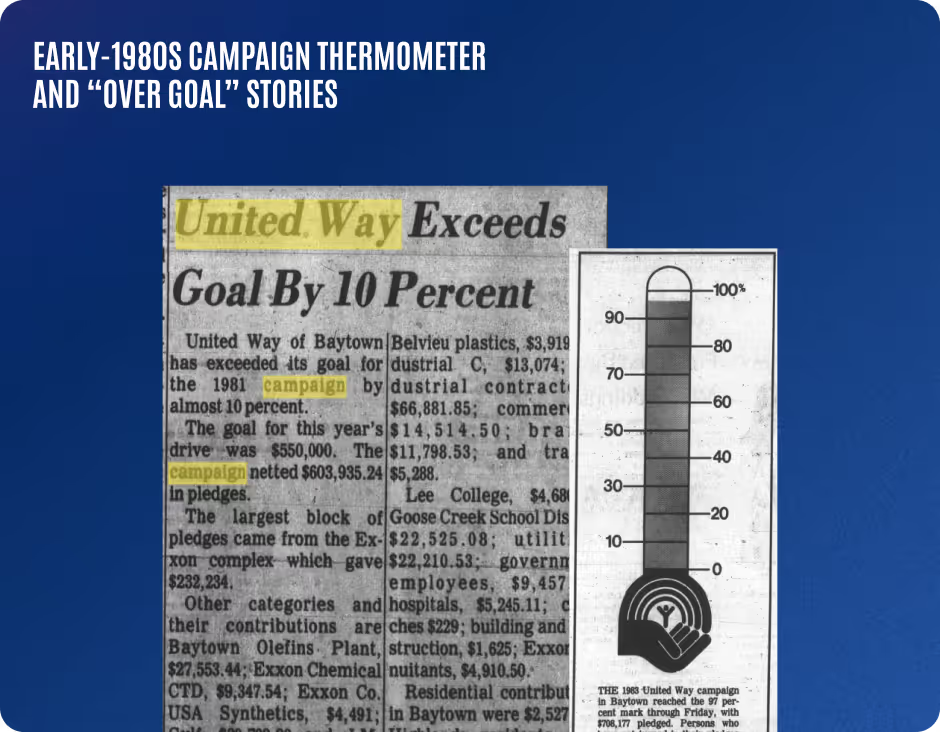

In the early 1980s, Baytown and Chambers County reached a new stage in their United Way story. Campaign thermometers in The Baytown Sun didn’t just creep toward the top—they regularly hit or crossed the goal line. Headlines celebrated “over goal” results not as rare surprises, but as something the community was starting to expect of itself.

This pattern of success said a lot about how far the united campaign had come. By this point, workplace drives were well established at the plants, in schools, banks, and offices. Campaign chairs knew how to organize strong teams. Agency stories were familiar and trusted. When United Way announced a new goal each year, people didn’t wonder if the campaign could do it—they asked what it would take this time to get there.

Reaching or surpassing goals year after year created a sense of stability that mattered deeply to partner agencies. Instead of wondering whether their doors would stay open, they could plan programs, hire staff, and serve more people with confidence. For families counting on those services—whether for child care, counseling, health care, shelter, or youth opportunities—that reliability meant everything.

These steady, successful campaigns also strengthened the bond between United Way and its donors. When the community saw goals set carefully and met consistently, it reinforced the idea that this was a well-run, dependable way to help. People could give through their paycheck or write a check at home and know their contribution was part of a proven, effective effort.

These milestones mark the moment when generosity and good systems combined into something powerful: a mature, dependable United Way that the community could count on—because it had already shown, again and again, that it could deliver.

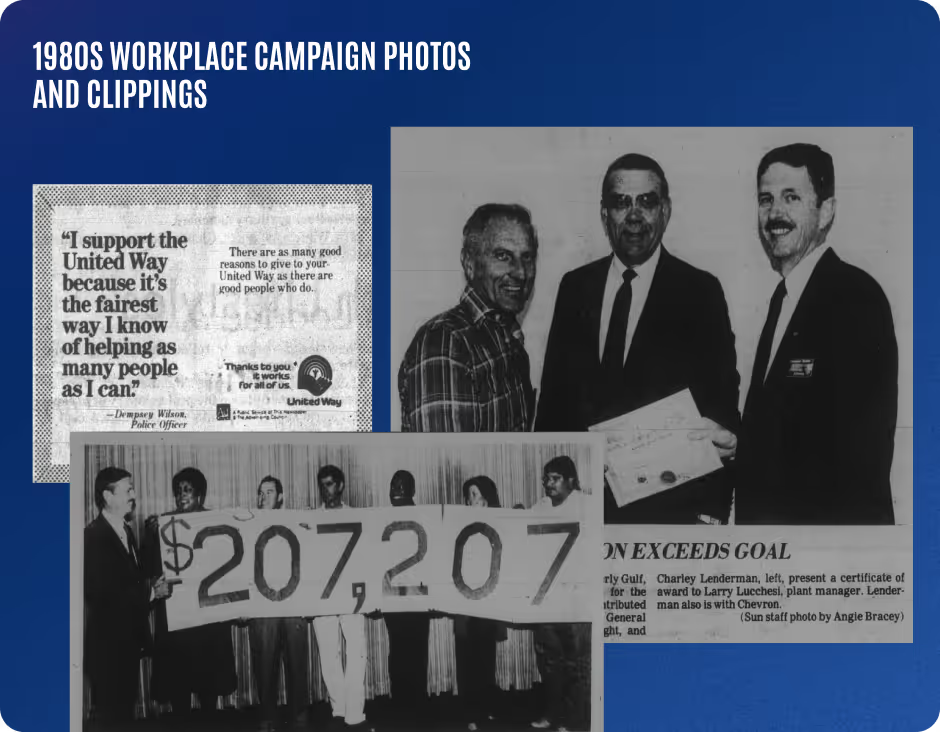

In the early to mid-1980s, the United Way campaign in Baytown and Chambers County didn’t just live in pledge forms and quiet conversations—it came to life on plant floors, in phone centers, and in office hallways. Companies like ExxonMobil, Chevron Philips, General Telephone, and others ran high-profile workplace campaigns that turned giving into a shared, visible experience.

At the refineries and chemical plants, campaign season meant kickoff rallies, safety-meeting presentations, and spirited competitions between departments. United Way volunteers showed slides or short talks about local agencies, making clear that gifts stayed right here—supporting neighbors, coworkers’ families, and the broader community. In offices and call centers, co-workers put up posters, tracked progress on thermometers, and celebrated when their teams reached 100% participation.

These corporate campaigns did more than raise large sums of money (though they certainly did that). They helped shape a culture of caring at work. When a supervisor or plant manager stood up and said, “I give, and I’m asking you to join me,” it sent a powerful message about what the company valued. When employees saw their donations highlighted in campaign totals and thank-you ads, they understood that their contributions—no matter the size—were part of something much larger.

For United Way, these partnerships meant stable, predictable support for a growing network of agencies. For the companies, it meant stronger ties to the community and a workforce that could feel proud of more than just the product they produced or the service they delivered.

On your history walk, this milestone shows how generosity became baked into the DNA of major employers in this area. It’s a reminder that some of the most important community-building doesn’t happen in big public moments, but in everyday decisions—like whole teams of employees choosing, together, to give through United Way.

In the mid-1980s, the United Way story in Baytown and Chambers County widened in an important way. The list of partner agencies grew to include names that many residents would come to know well: DePelchin Children’s Center, Bay Area Rehabilitation Center, Big Brothers Big Sisters, Bayshore Mental Health, the Women’s Center, and others. Each new partner represented a deeper, more nuanced understanding of what it takes for individuals and families to truly thrive.

These agencies brought specialized strengths. DePelchin offered support for children and families working through trauma, adoption, and behavioral challenges. Bay Area Rehab helped neighbors recover from injury or disability and regain independence. Big Brothers Big Sisters paired young people with caring adult mentors. Bayshore Mental Health addressed emotional and mental wellness—needs that had too often stayed in the shadows. The Women’s Center provided safety, advocacy, and a lifeline for survivors of domestic violence and abuse.

By welcoming these partners into the United Way family, the community was quietly saying: we see you, and we know your needs are real. It also meant that when someone called a United Way–funded agency for help, that agency stood within a larger network, supported not just by one grant or one donor, but by thousands of neighbors giving through the united campaign.

For donors, the expanding roster clarified something important. United Way wasn’t only about one kind of help; it was about the whole person and the whole family—body, mind, safety, and opportunity. A single paycheck pledge now reached further into the community’s most complex challenges.

On your history walk, this milestone shows United Way growing not just in size, but in depth. By the mid-1980s, the circle of care had widened significantly, making it more likely that when someone in Baytown or Chambers County reached out for help, there was a United Way–supported program ready to answer.

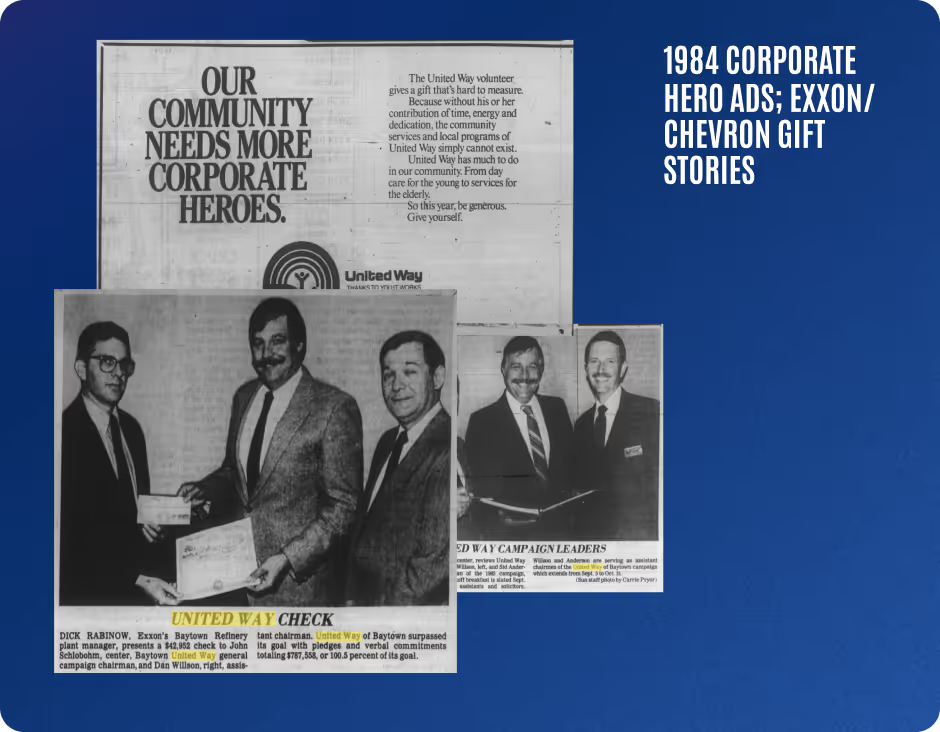

In 1984–1985, United Way’s partnership with local industry stepped into the spotlight in a new way. Newspaper ads and stories began celebrating “corporate heroes”—companies whose generosity and leadership were helping drive the campaign forward. Names like Exxon, Chevron, and other major industrial employers appeared alongside big numbers and smiling employee groups, reinforcing a powerful message: strong companies and strong communities go hand in hand.

These weren’t quiet, behind-the-scenes checks. They were visible commitments, highlighted in photos of plant managers presenting campaign totals, articles praising high employee participation, and ads thanking companies for going above and beyond. The public recognition made something clear: corporate giving wasn’t just philanthropy—it was part of what it meant to be a responsible neighbor in Baytown and Chambers County.

Inside the plants and offices, these major gifts were rooted in thousands of individual choices. Employees pledged through payroll deduction. Campaign captains organized presentations, contests, and events. Supervisors encouraged their teams to participate. When the final numbers were tallied and a company was named a “corporate hero,” it wasn’t just management being honored—it was every worker who had checked the box and said, “Yes, I’ll help.”

For United Way, these large industrial contributions provided crucial stability. They helped ensure consistent funding for agencies serving children, seniors, survivors of violence, people with disabilities, and families in crisis. For the companies, being recognized as corporate heroes deepened their connection to the community and to the lives of their own employees outside the workplace.

On your history walk, this milestone shows how the mid-1980s crystallized a culture of corporate citizenship. It’s a reminder that some of the most transformative community investments happen when businesses decide that success isn’t measured only in barrels, units, or profit—but also in how well their neighbors are doing, and how boldly they choose to LIVE UNITED.

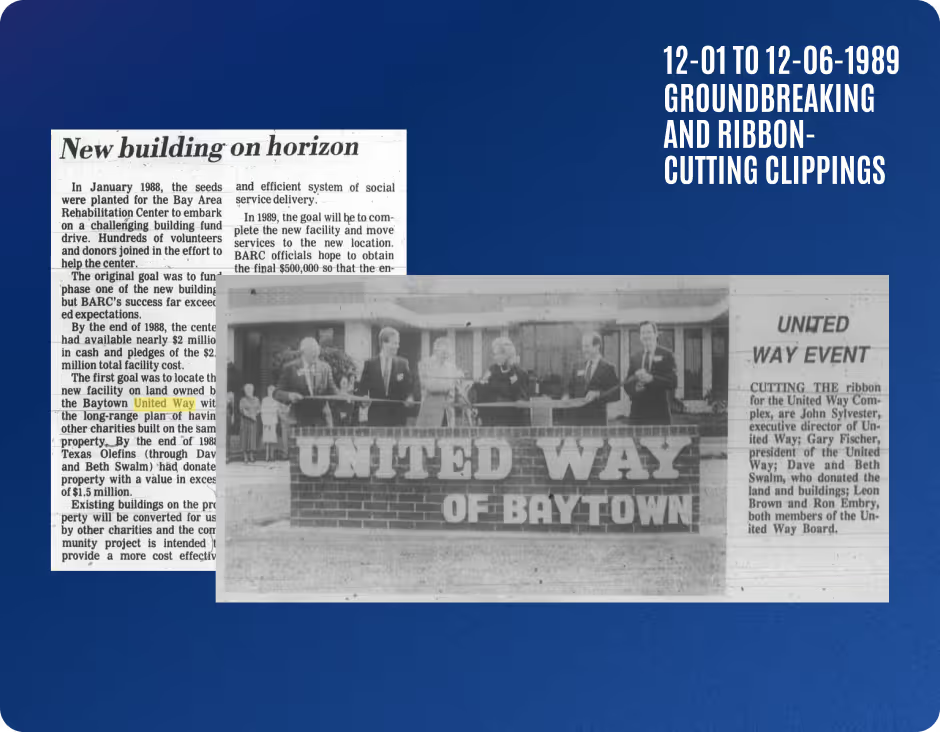

The late 1980s were a time of big moves—literally and figuratively—for United Way in Baytown. In 1989, two milestones came together: the opening of a new United Way building on Decker Drive and the community’s first million-dollar campaign.

The new building meant more than office space. It was a visible, permanent sign that United Way was here to stay—a place where agency partners, volunteers, and neighbors could come together. Ribbon-cutting photos captured local officials, board members, and donors celebrating not just bricks and mortar, but a shared investment in the future.

At the same time, the campaign thermometer climbed higher than ever before. When the final pledges were tallied, United Way announced that the community had topped $1 million. For donors who remembered the early Community Chest days, the comparison was staggering: from tens of thousands to over a million in just a few decades.

That first million-dollar year changed expectations. It showed that Baytown and Chambers County didn’t just support United Way—they relied on it to sustain a wide network of services: shelters, youth programs, senior services, health care, and more. The combination of a new home and a record campaign sent a clear message: this community believes in the power of living united, and it’s willing to put real resources behind that belief.

The 1990s

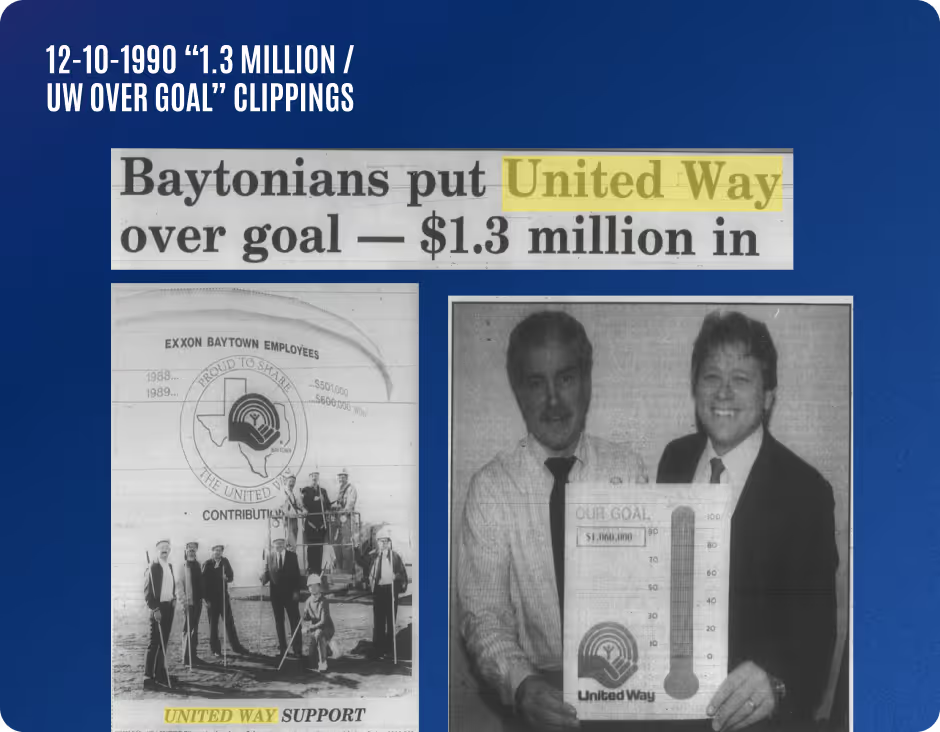

In 1990, United Way in Baytown and Chambers County hit a milestone that would have seemed almost unimaginable in the early Community Chest days: the annual campaign climbed over $1.3 million. Headlines celebrated that United Way was “over goal,” marking not just a successful year, but the continuation of a new era—one where seven-figure fundraising had become the community’s standard.

Behind that big number was a familiar but powerful story. At the refineries and plants, employees signed pledge cards in breakrooms and at safety meetings, often encouraged by coworkers who served as campaign captains. In schools, banks, and small businesses, staff meetings included a few minutes to talk about United Way and the agencies it supports. Retirees mailed in checks. Civic clubs and churches sponsored events and special offerings. Everyone did their part, and together those individual choices added up to $1.3 million in local impact.

For partner agencies, surpassing that level of giving meant stability and opportunity. Programs serving children, seniors, survivors of violence, people with disabilities, and families in crisis could plan more confidently, deepen services, and reach more neighbors. The community wasn’t just putting out fires—it was investing in a stronger, more resilient safety net.

Equally important, the 1990 campaign helped cement a sense of identity. Baytown and Chambers County were now firmly a “million-dollar United Way community”—a place where generosity was not the exception, but the expectation.

On your history walk, this milestone marks a moment of maturity and momentum. It shows a community stepping into the 1990s not cautiously, but confidently—proving once again that when people here are invited to LIVE UNITED, they respond at a scale that truly changes lives.

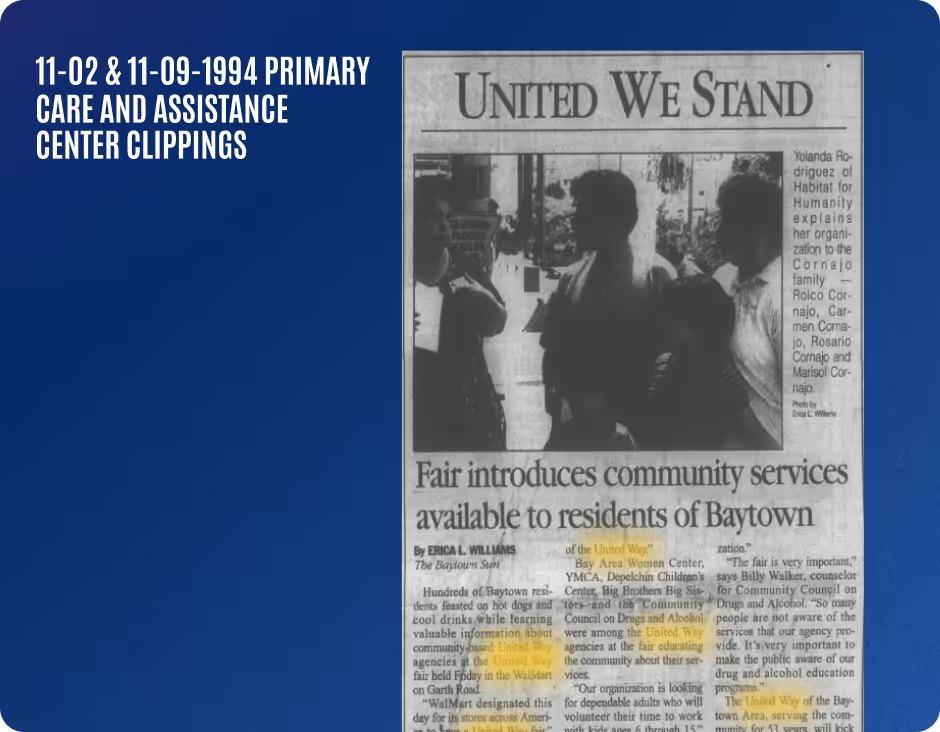

In the mid-1990s, United Way’s role in Baytown and Chambers County took a significant step beyond writing checks. Recognizing that too many neighbors were struggling to access basic medical care and crisis assistance, United Way helped bring partners together to open new primary care and community assistance centers.

The need was clear. Families without insurance or with very limited coverage often delayed going to the doctor until small issues became major problems. People facing job loss, rising bills, or housing instability were bouncing from one agency to another, trying to figure out where to start. United Way could see that the community needed not just more funding, but smarter connections.

So instead of acting only as a funder, United Way leaned into its strength as a convener. It helped gather hospitals, clinics, nonprofits, churches, and local officials around the same table. Together, they planned centers where residents could receive primary medical care, referrals, and assistance with basic needs under one roof—or through closely coordinated partners.

When the centers opened, they represented more than a new program. They were proof that the community could design practical solutions to complex problems when everyone shared ownership. A person might walk in for medical care and leave with information about food assistance, counseling, or help with utilities. The goal was simple but powerful: no wrong door.

For United Way, these centers marked a shift from “supporting services” to shaping the system those services operate within.

On your history walk, this milestone shows United Way stepping fully into its role as a community catalyst—using its relationships, credibility, and big-picture view to help create places where health, stability, and hope could begin to take root, all in one stop.

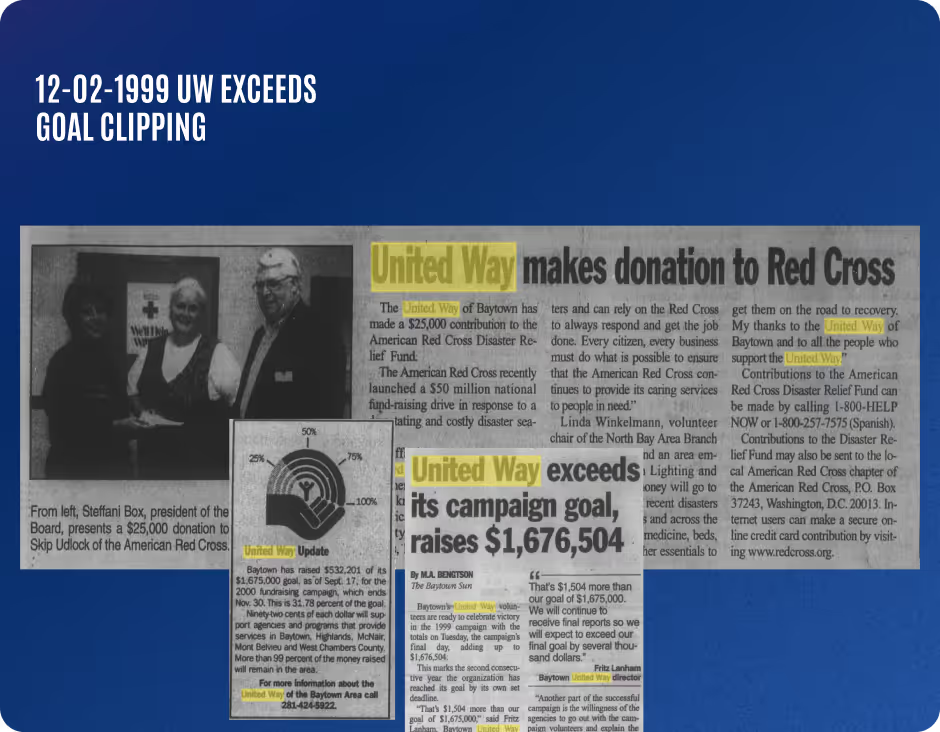

On December 2, 1999, as the community prepared to step into a new century, United Way of Greater Baytown Area & Chambers County closed out the 1990s with a familiar but still powerful headline: the campaign had exceeded its goal—again. It was more than a single year’s victory; it was a statement about the kind of community Baytown and Chambers County had chosen to be.

All decade long, United Way had been building on its million-dollar momentum. Workplaces refined their campaigns, agencies sharpened their stories, and volunteers learned how to reach new donors and re-engage long-time supporters. By the time the 1999 campaign rolled around, there was a strong sense of shared ownership: this wasn’t just United Way’s campaign—it belonged to everyone.

When the final pledges were totaled and the announcement was made, exceeding the goal felt like a community-wide exhale and a cheer rolled into one. It meant that agencies serving children, seniors, families in crisis, people with disabilities, and survivors of violence could enter the new millennium with stability instead of uncertainty. It meant that dreams of expanding programs, reducing waitlists, and innovating new services didn’t have to be put on hold.

Just as importantly, the 1999 over-goal result helped set the stage for the multi-million-dollar campaigns of the 2000s. It showed donors and leaders alike that this community was ready not only to meet big goals, but to imagine bigger ones. The habit of generosity, practiced year after year, had become part of the local identity.

On your history walk, this milestone marks a fitting finale to the 1990s: a community closing out the century the same way it had faced so many challenges before—together, over goal, and looking ahead to what more could be done by living united.

The New Millenium 2000s

By January 2002, the network of services in Baytown and Chambers County was rich and diverse—but for someone in crisis, it could feel like a maze. If you needed food, rent help, counseling, or care for an aging parent, how were you supposed to know where to begin?

That’s why the local promotion of the 2-1-1 helpline was such a big turning point. With a simple message—dial 2-1-1—United Way and its partners offered residents a new promise: you don’t have to figure this out alone.

When people called 2-1-1, they reached trained specialists who knew the landscape of local resources: United Way–funded agencies, faith-based programs, government services, and other community supports. Callers didn’t need to know which program did what. They just needed to share what was going on—“I just lost my job,” “I can’t pay the light bill,” “My mom needs help at home,” “I’m overwhelmed and don’t know where to turn”—and the 2-1-1 specialist helped map out next steps.

For many families, that single call turned panic into a plan: a referral to a food pantry and utility assistance, information on counseling or support groups, a connection to child care or health services. It was a bridge between need and help, built on the quiet, steady infrastructure United Way had been investing in for decades.

Promoting 2-1-1 also deepened United Way’s identity as a connector, not just a funder. It made the united network of services more accessible, more humane, and more efficient—especially for those facing crisis for the first time.

On your history walk, this milestone shows how, in 2002, the community took a big step toward making help easier to find. With three simple numbers—2-1-1—Baytown and Chambers County told every neighbor: when you’re not sure where to turn, start here, and we’ll help you find the way.

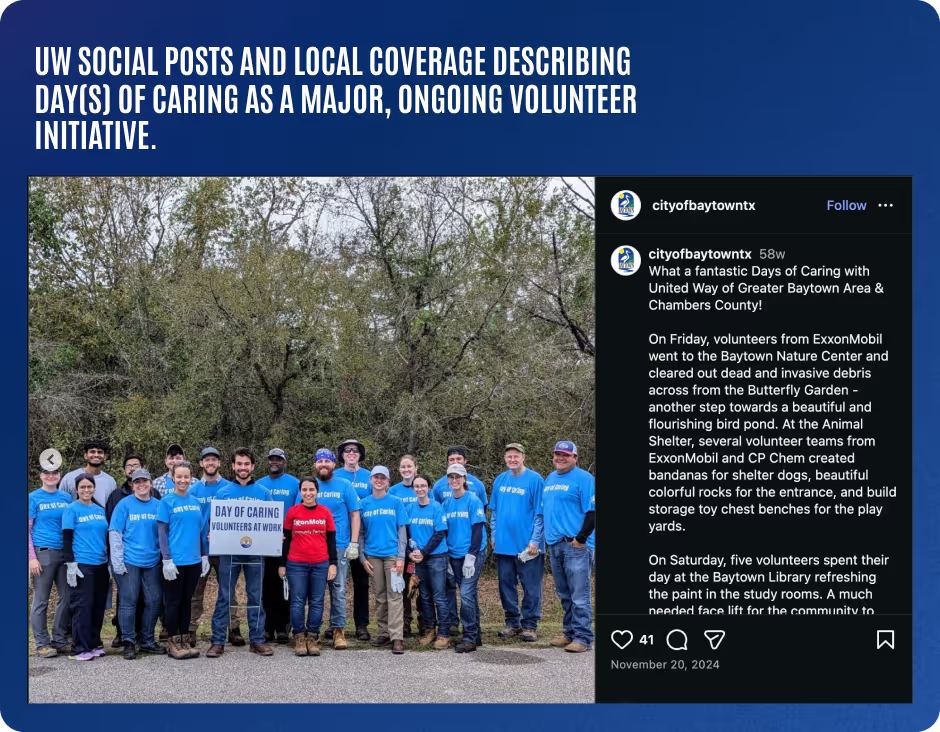

In the early 2000s, United Way’s impact in Baytown and Chambers County wasn’t just measured in dollars raised—it was measured in hands painted, dirt under fingernails, and hours of sweat poured into local projects. That’s when Day of Caring really began to grow, bringing teams from companies like UPS, Exxon, and other corporate partners out of their offices and plants and into schools, parks, and nonprofit sites across the community.

On Day of Caring mornings, volunteers in matching t-shirts would gather, grab tools and assignments, and fan out to dozens of locations. Some repainted classrooms or community rooms. Others built ramps, cleaned up playgrounds, sorted donations, or tackled landscaping at shelters and youth centers. Agencies that often operated on tight budgets suddenly had a small army of helpers for the projects they could never quite get to on their own.

For companies, Day of Caring offered something powerful that a payroll deduction alone could not: a chance for employees to see and feel what their United Way support made possible. A UPS driver might spend the day building shelves at a food pantry. An Exxon engineer might read with children at an after-school program. Coworkers who usually only saw each other in meetings found themselves side by side with paint rollers, discovering new shared purpose.

For United Way, these days showcased what it truly means to LIVE UNITED—giving, yes, but also serving, showing up, and building relationships between volunteers, agencies, and the people they serve.

On your history walk, this milestone shows how, in the early 2000s, Day of Caring transformed United Way from something people give to into something they could do together—a tangible reminder that when we roll up our sleeves as one community, change happens faster and hope feels closer.

In the mid-2000s, the United Way campaign in Baytown and Chambers County started to look a little different—and that was a very good thing. Alongside long-time industrial and corporate partners, new workplaces like Best Buy, Koppel Steel, and other emerging employers began to run United Way campaigns of their own.

Each new workplace meant more than just an additional line on a donor list. It represented a widening circle of ownership. When a retail team at Best Buy set a campaign goal, or when employees at Koppel Steel organized their first pledge drive, they were saying, “We’re part of this community, too—and we want to help take care of it.” Younger workers, new residents, and employees outside the traditional plant-and-office mix now had a clear path to participate through their paycheck.

Campaign photos and clippings from this period show store associates, steelworkers, and managers presenting checks, celebrating milestones, or posing at agency sites. These images tell the story of a donor base that was becoming more diverse and resilient. Instead of relying heavily on a few major employers, United Way was building a broader foundation—one that could better withstand economic shifts and reach new networks of people who hadn’t been asked to give in this way before.

For partner agencies, this diversification meant greater stability and the potential for growth. For United Way, it validated years of relationship-building and outreach: the message of living united was resonating in new sectors and new workplaces.

On your history walk, this milestone shows how, in the mid-2000s, United Way GBACC expanded from “the campaign at the plants” into a campaign for the whole local economy—inviting big employers, small teams, and new businesses alike to stand together for the community they all call home.

In 2008, two powerful forces arrived in Baytown and Chambers County at almost the same time: a bold new message and a brutal storm.

First came the message. Across the country, United Ways rolled out a new call to action: LIVE UNITED. Locally, the words began appearing on billboards, t-shirts, posters, and workplace materials. LIVE UNITED wasn’t just a slogan—it was an invitation to see the community differently: not as “us and them,” but as all of us together, responsible for one another’s well-being.

Then, that same year, Hurricane Ike slammed into the Texas Gulf Coast. High winds and storm surge damaged homes, businesses, schools, and vital infrastructure across Baytown and Chambers County. Families who had never asked for help suddenly found themselves tearing out wet carpet, sorting through ruined belongings, and wondering where to turn next.

United Way and its partner agencies stepped quickly into the gap. Shelters were supported. Food, clothing, and emergency supplies reached families who’d lost everything. Caseworkers helped residents navigate insurance, FEMA, and the long, confusing road to recovery. Churches, nonprofits, and volunteers came together in ways that made the LIVE UNITED message feel less like branding and more like a description of what was actually happening.

In many ways, Ike became a proving ground. It showed that LIVE UNITED wasn’t just about giving during campaign season—it was about neighbors checking on neighbors, companies loaning trucks and teams, agencies coordinating services, and United Way helping to connect all the pieces.

On your history walk, this milestone shows 2008 as a hinge year. LIVE UNITED arrived on paper and on t-shirts—but Hurricane Ike etched it into the community’s memory. In the face of wind, water, and loss, Baytown and Chambers County chose to live the message out loud: we will get through this, together.

The 2009–2010 campaign unfolded during one of the most difficult economic periods in recent memory. Families were tightening budgets, companies were watching every dollar, and the need for help was rising. In that context, United Way’s announcement that the campaign had raised about $2.856 million, surpassing its $2.65 million goal, felt nothing short of remarkable.

The result wasn’t accidental. Workplace campaigns leaned into creativity—jeans days, cook-offs, fun runs, and raffles. Longtime donors increased their giving when they could. New donors gave what they were able, often saying, “I can’t give a lot, but I still want to help.” Agency partners told powerful stories about neighbors facing job loss, illness, or housing instability—and how United Way funding kept critical services open.

The campaign’s success sent an important signal: even in hard times, this community chooses solidarity over scarcity. Rather than pulling back, residents leaned in, understanding that their neighbors might need United Way’s partner agencies more than ever.

For today’s history walk, this milestone shows that the generosity Baytown and Chambers County are known for isn’t just a feature of boom years. It’s a defining part of who we are, especially when circumstances are tough.

In the late 2000s, a quiet shift was taking place in the way United Way of Greater Baytown Area & Chambers County invested donor dollars. While the campaign still supported a broad mix of services, more and more energy and funding began flowing toward health, mental health, and education programs. Looking back now, you can see the early outlines of the strategic focus areas that would come later.

Agency lists and news clippings from this period show growing support for counseling and mental health services, primary and preventive health care, and programs that help children succeed in school—tutoring, mentoring, after-school and summer enrichment. United Way was listening closely to what the community was experiencing: families stretched thin, kids struggling to stay on track, and neighbors carrying heavy emotional burdens without enough support.

By elevating health and education partners, United Way was quietly making a statement: it’s not enough to respond to crisis—we have to strengthen the foundation. Helping a child stay on grade level, or ensuring a parent can access mental health care, can change the entire trajectory of a family’s future. The investments of this era began to reflect that long-term view.

For agencies, this support meant the ability to expand counseling hours, add new program slots for students, or deepen outreach to families who might never have sought help before. For donors, it created a clear sense that their gifts were doing more than meeting immediate needs—they were helping neighbors build healthier, more stable lives from the inside out.

On your history walk, this milestone marks the “before” picture of what would eventually become named focus areas like Youth Opportunity, Healthy Community, and Community Resilience. In the late 2000s, United Way was already moving in that direction—choosing to invest not only in emergency relief, but in the health, learning, and well-being that give every neighbor a better chance to thrive.

The 2010s

As the new century unfolded, it became increasingly clear that the needs and strengths of Chambers County were deeply intertwined with those of Baytown. Families lived on one side of the county line and worked on the other. Children attended schools across districts. Storms and economic shifts never stopped at jurisdictional boundaries.

In the early 2010s, United Way formally recognized what had long been true in practice: it was serving a bi-county community. The organization adopted the name United Way of Greater Baytown Area & Chambers County. With that change came not only new branding, but a clearer commitment to equitable service across the region.

The expanded name signaled to donors and partners that Chambers County wasn’t an add-on; it was central to the mission. Campaign goals reflected the combined needs of both sides of the bay. Agency partners in Mont Belvieu, Anahuac, and other communities became fully woven into United Way’s network of support.

This milestone matters because it captures the heart of United Way’s approach: go where the need is, and build bridges between communities. The name change acknowledged that Baytown’s story and Chambers County’s story are deeply connected—and that United Way would be there for both.

In 2014, United Way of Greater Baytown Area & Chambers County gathered for its annual campaign kickoff with a mix of excitement and determination. The goal on the board—$3.2 million—was more than a number. It was a statement about who this community believed it could be, and what it was willing to do for its neighbors.

At the center of that moment were visible leaders like Guido Persiani, along with major corporate partners such as Bayer and other longtime supporters. Their presence at the podium wasn’t just ceremonial. When leaders like Persiani and key corporate champions stood up and said, “We’re committed,” it sent a clear signal to employees, volunteers, and the broader community: this campaign matters—and we’re in it together.

Kickoff coverage highlighted both the ambition and the partnership behind the goal. Corporate teams talked about their plans for workplace drives—presentations, challenges, raffles, and events that would make giving fun and meaningful. Agencies shared stories of families finding stability, children succeeding in school, and seniors staying connected and cared for because of United Way support.

The $3.2 million target reflected a deep understanding of local needs. From health and mental health care to education, basic needs, and crisis response, agencies were being asked to do more in a changing economic and social landscape. The campaign invited everyone—from plant workers to professionals, retirees to young employees just starting out—to be part of the solution.

This milestone represents a mature United Way stepping forward with strong volunteer and corporate leadership, bold goals, and a clear sense of shared responsibility. The 2014 campaign launch shows what happens when vision, credibility, and community pride come together: a whole region deciding, out loud, that it will LIVE UNITED at a level worthy of its people and their potential.

On April 2, 2015, United Way of Greater Baytown Area & Chambers County shared a milestone that spoke volumes in a single line: the community had topped $3 million in giving for the third consecutive year. It wasn’t just another over-goal headline—it was proof that this level of generosity was no longer a one-time achievement, but part of the community’s new normal.

Reaching $3 million once takes an enormous amount of effort: strong workplace campaigns, committed corporate partners, passionate volunteers, and donors willing to stretch. Doing it three years in a row means something deeper has taken root. It means that giving at this scale has become part of the culture—part of how Baytown and Chambers County understand who they are.

Behind that third consecutive $3 million year were countless quiet decisions. Employees said yes to increasing their payroll deductions, even by just a few dollars a paycheck. Retirees continued to give, long after their working years were over. Companies matched gifts, loaned executives, and encouraged their teams to get involved. Volunteers led tours, told stories, and reminded coworkers and friends why United Way matters.

For partner agencies, three strong years in a row meant more than full budgets. It meant the ability to think long-term: adding critical staff, piloting new programs, deepening outreach to underserved neighborhoods, and measuring outcomes in ways that could drive real systems change. For the families walking through agency doors, it meant programs would be there not just today, but tomorrow and the year after that.

This benchmark notes a moment of sustained strength. It shows a community that didn’t stop at reaching a big number, but chose to stay there—to keep investing at a level that matched the size of its challenges and its hopes. Three consecutive years above $3 million is more than a fundraising statistic; it’s a portrait of a community that has decided, together, to LIVE UNITED in a deep and lasting way.

In 2016–2017, Baytown became the testing ground for a bold new idea in cancer prevention. The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, sponsored by ExxonMobil, launched Be Well™ Baytown—a long-term, place-based initiative designed to stop cancer before it starts by changing the everyday environments where people live, learn, work, and play.